Description

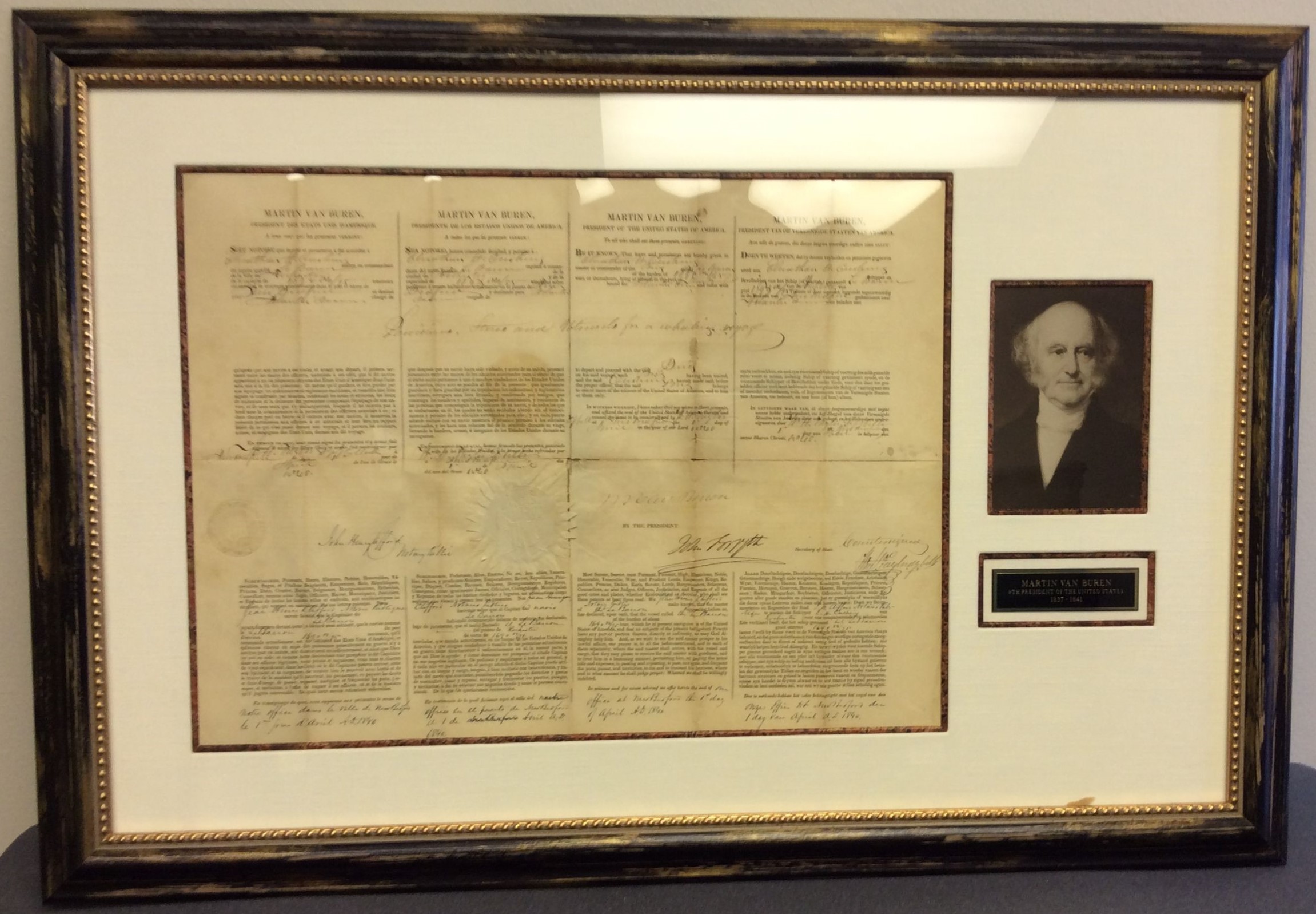

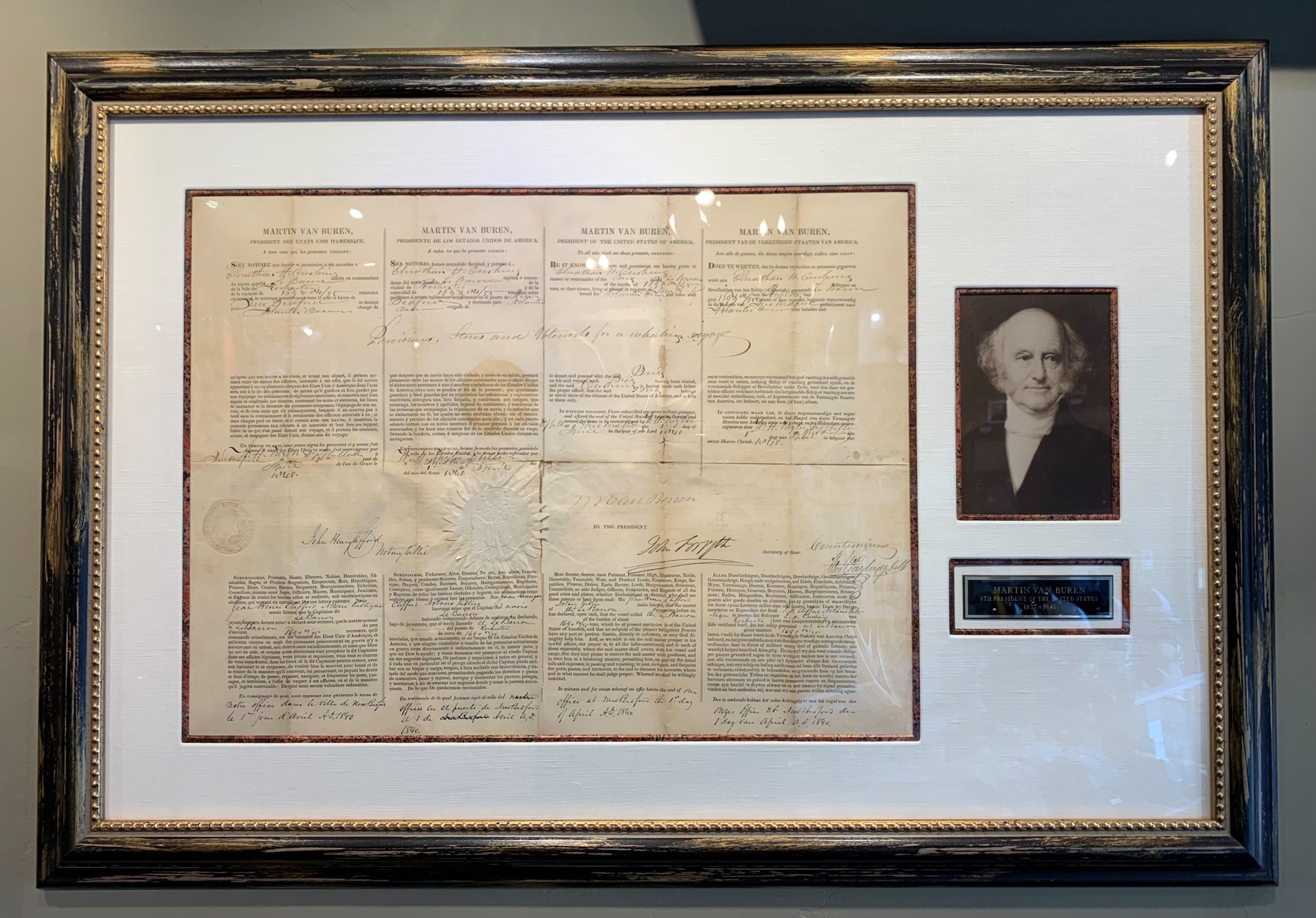

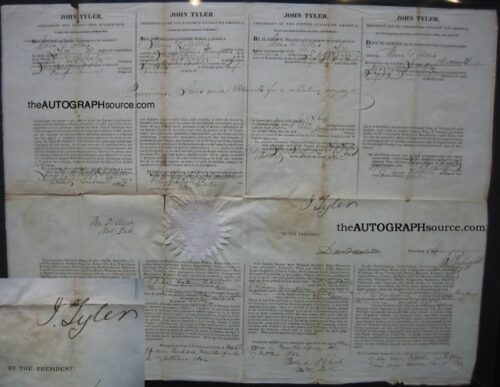

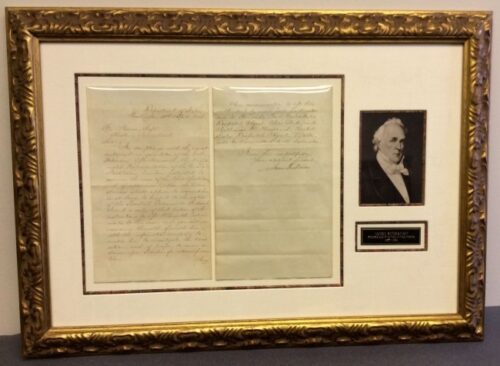

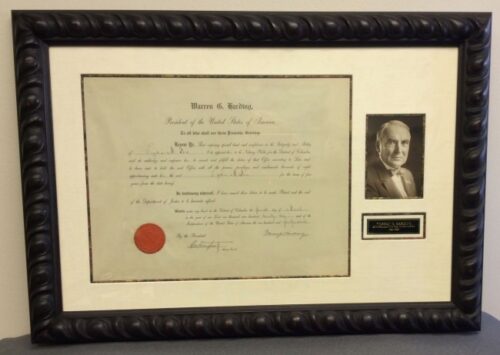

An 1840 Four Language Ship’s Passport (or Four Language Sea Letter) signed by United States of America President Martin Van Buren (8th President) .

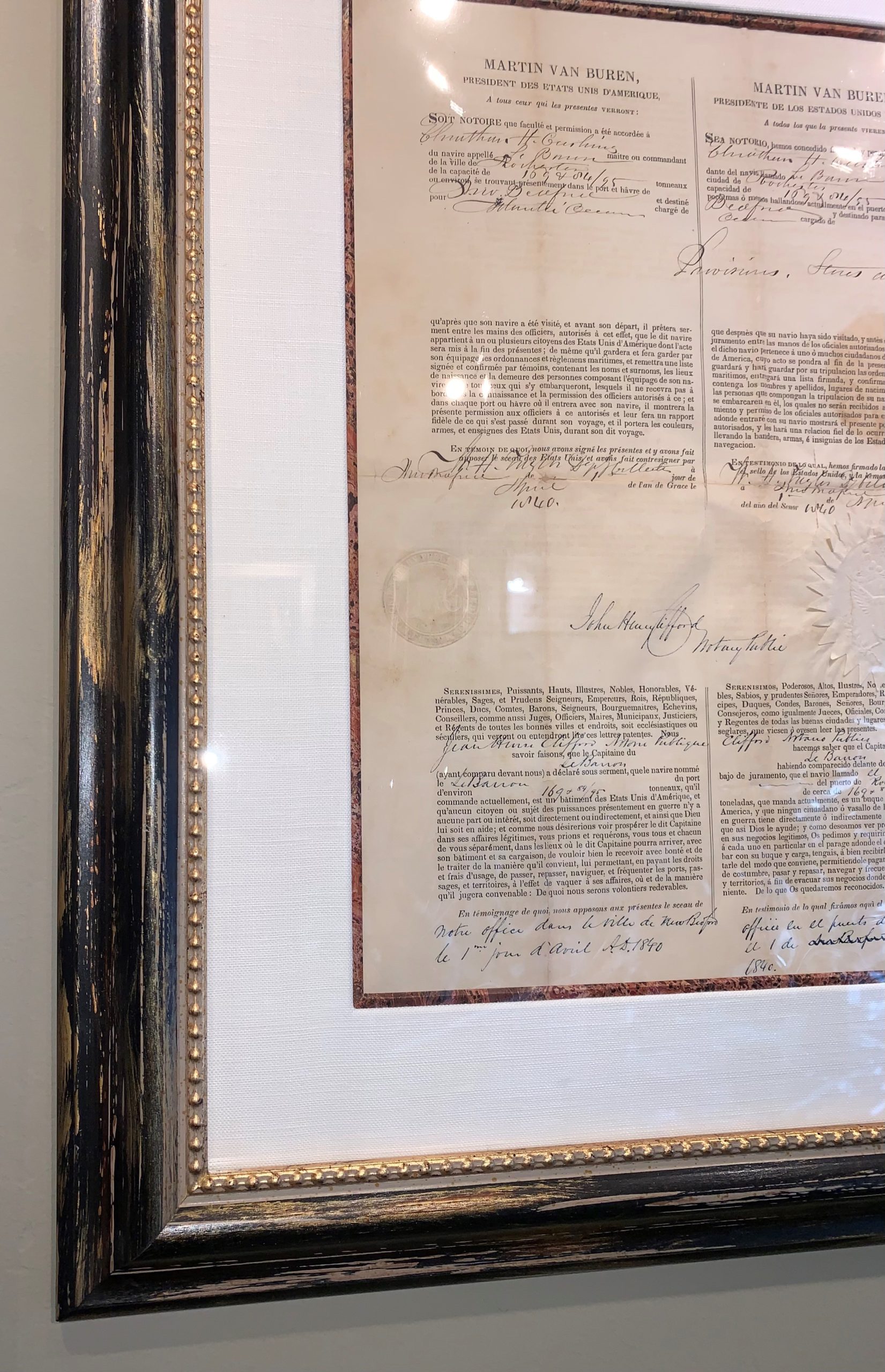

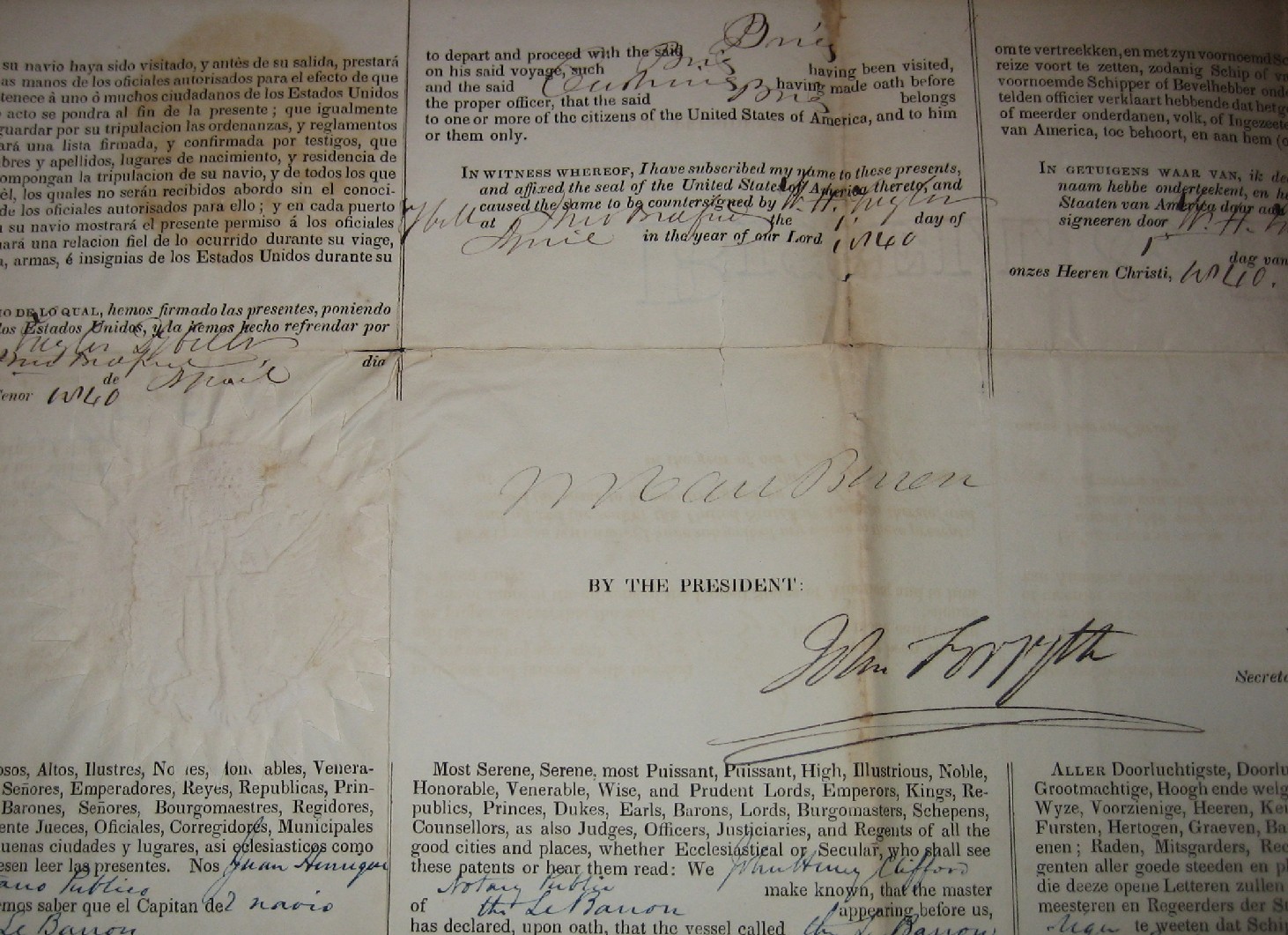

A Four Language Ship’s Paper (passport) signed in black “Martin Van Buren” as President. The passport is for a ship named “Le Baron”, leaving the Port of New Bedford, Massachusetts, bound for the Atlantic Ocean with provision, staves, etc. for a Whaling Voyage.

The document is written in the four major languages of the day — French, Portuguese, English, and Dutch, and provides the protection of the U.S. Government for the ship for this specific voyage. This paperwork also proves that the ship is not running contraband.

The US seal is completely intact. The second seal is a Notary Seal from New Bedford. The document has a round stain from where the paper was folded against the US seal, has some tearing on the folds, and some minor wear to edges. Overall presents very well. The Van Buren signature is a shade light, but very legible.

Dated April 1, 1840. The unframed document measures 20.5″ x 16.5″. The framed dimensions are 35.5″ x 24″. The museum caliber frame is included in the price.

Sold with Letters of Authenticity from both The Autograph Source and independent third-party authenticator Beckett Authentication Services.

_____________

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ABOUT SHIPS PAPERS / SEA LETTERS:

The term “Sea Letter” has been used to describe any document issued by a government or monarch to one of its merchant fleet, which established proof of nationality and guaranteed protection for the vessel and her owners. However, it the Sea Letter use by the United States after 1789 that is of particular interest here.

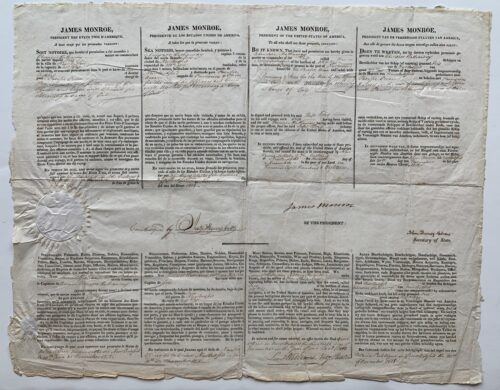

The 1822 edition of The Merchants and Shipmaster’s Assistant described the Sea Letter as “a document which specifies the nature of the cargo and the place of destination, and says that is was only required for vessels bound to the Southern Hemisphere. In 1859 the document was defined as part of the ship’s papers when bound on a foreign voyage, it is written in four languages, the French, Spanish, English, and Dutch, and is only necessary for vessels bound round Cape Horn and the Cape of Good Hope.”

The Sea Letter was a remarkably standardized document, which changed little during the time that it was used. Usually printed on heavy grade paper, approximately 16″ x 20″ in size, the first Sea Letters carried only three languages instead of four. However, they soon became known as Four Language Sea Letters.

The statement within the document conveys in part that the vessel described is owned entirely by American citizens, and requests that all Prudent Lords, Kings, Republics, Princes, Dukes, Earls, Barons, Lord, Burgomasters, Sheens, Consolers, etc., treat the vessel and her crew with fairness and respect.The signatures of the President of the United States, the Secretary of State, and the customs collector appear in the middle portion of the document.

Sea Letters are mentioned in the formative maritime legislation forged by the new Federal governments. They provided additional evidence of ownership and nationality, but the criteria by which a shipmaster utilized one document over the other is not completely clear. It was explained at the time that both documents were rendered necessary of expedient by reason of treaties with foreign powers, a statement which suggests that certain nations required a particular document because of existing agreements with the United States.In any case the Sea Letter was valid for only a single voyage, and a bond does not seem to have been required. Neither was it to be returned to the collector when the voyage was completed. Indications are that, as the years progressed, Sea Letters were being used more often by whaling ships than by merchant vessels, perhaps because American whalers fished in areas where this document was preferred as proof of national origin.

By providing a statement of American property, signed by the President of the United States, the Mediterranean Passport and the Sea Letter were intended to confirm our status as a neutral nation, when international conflict put added dangers on America’s commerce at sea. By mid-century, however, much of what had previously threatened our shipping was being neutralized by the expanding power of the United States.As our merchant fleet became more secure, fewer ship owners and shipmasters considered these documents as necessary to guarantee their rights and safety in foreign lands.*

Both pieces were considered important parts of a ship’s papers in the 1800s. They were kept aboard ship during the voyage and deposited, along with the Registry Certificate, with the appropriate U.S. consular authority anytime the vessel was in a foreign port.Today they are considered to be important documents in any maritime collection. However, they are also highly valued by autograph collectors and investors, which keeps many fine pieces in private hands.

*It is important here to note that these documents were intended only to protect the vessel from capture of destruction by providing American, i.e., nonbelligerent, ownership. American crew members aboard these ships were still vulnerable to impressment, especially if they did not carry their own personal protection certificates as proof of citizenship.